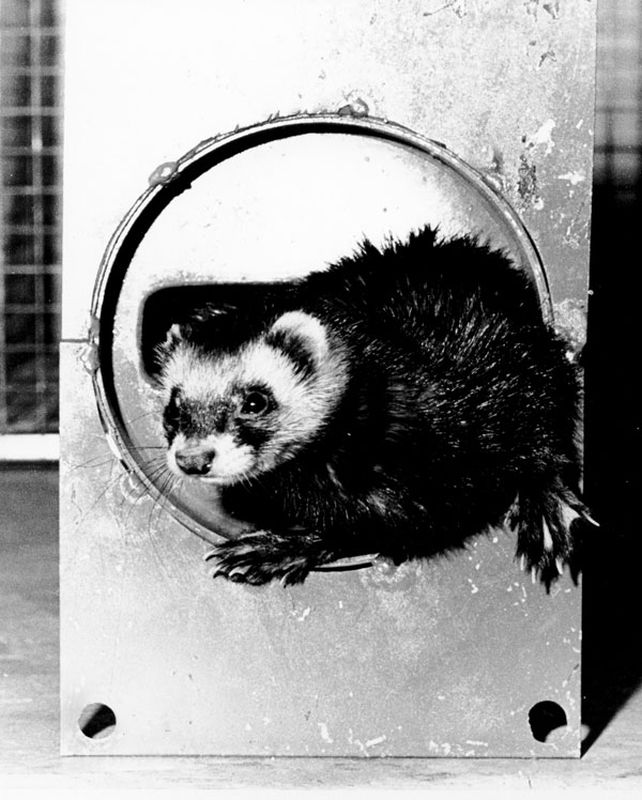

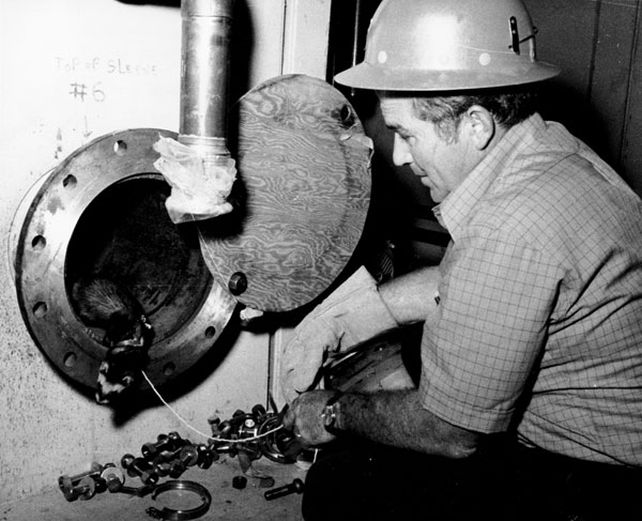

Felicia the ferret. (Tim Fielding/NAL)

Felicia the ferret. (Tim Fielding/NAL)

Decades ago, regulations for laboratory maintenance were not quite as stringent as they are today. This, we assume, is at least partially what led the great minds at what was then the US National Accelerator Laboratory, now Fermilab, to an ingenious solution for cleaning a particle accelerator back in 1971.

It was February. The Main Ring particle accelerator at the NAL's Meson Laboratory was fresh out of the wrapper, and physicists were keen to start running it through its paces.

This $250 million piece of equipment consisted of a 4-mile (6.4-kilometer) tube along which, they hoped, 1,014 powerful magnets would help steer and accelerate protons to energies up to 200 billion electron volts. The scientific prospects were incredibly exciting.

By late April, things were not looking quite so rosy. Six days after the final magnet was installed, two of the things were found shorted to the ground. This was no trivial matter. Most of the magnets were each around 20 feet long, with a weight of 12.5 tons. It took some time to replace the two magnets… But then it happened again. And again. In total, the facility had to replace around 350 magnets.

Eventually, the team traced the problem to one of contamination. Tiny scrap metal shavings had been left in the accelerator. The accelerator tube had the diameter of a tennis ball. This posed a dilly of a pickle: How to get the shaving out? Physicist Ryuji Yamada proposed pulling a magnet through the tubes. Not a bad idea, but who would do the pulling?

British physicist Robert Sheldon – a very inventive fellow – hit upon a solution.

"In his part of Yorkshire, hunters used ferrets," computer scientist Frank Beck recalled in 2016.

"Ferrets are weasel-like mammals who enjoy going down tunnels and flushing out rabbits. A ferret would not hesitate to run down the inside of the stainless steel tube, even if that involved a long journey into the unknown. Furthermore, it would be a sort of green solution to a technical problem, and everybody liked the idea of that."

The Designer of the Main Ring, Wally Pelczarski, who had been tasked with designing a mechanical ferret to clean the tube, contacted the Wild Game and Fur Farm in Gaylord, Minnesota, and asked them for the smallest ferret they had. In exchange for just $35, they sent Felicia. At just 15 inches long, Felicia was a particularly small ferret, just right for the tiny tunnel that needed cleaning.

Felicia was fitted with a diaper to prevent defecation-related particle accelerator mishaps and a leather harness. Then, the researchers trained her to travel through dark tunnels while wearing the harness, which had a strong string attached to it.

She would scamper from one end of the 300-foot sections of the tunnel to the other, receiving a reward of chicken, liver, fish heads, or hamburger meat once she completed a section. An engineer at the end would tie a cleaning-fluid-soaked swab to the string, to be drawn back through the tunnel by humans at the other end to collect detritus.

Apparently, it worked pretty well, and the scientists could clear out the tunnels with a little fuzzy help. Over time, however, their needs exceeded Felicia's capabilities, and engineer Hans Kautzky developed a new solution. He attached Mylar disks to a flexible cable that was pushed through the pipes using compressed air, and Felicia retired after a dozen or so runs.

It also turned out that there were multiple reasons for the magnets' failing, and metal shavings were not the prime culprit.

"The main reason was poor quality control in making joints for the water-cooled copper conductors," Yamada recalled. "The mating surfaces of a butt weld joint were sometimes not completely parallel, and the resulting joint might have a small, wedge-shaped gap. Later, improved welding with an inserted pipe was used."

Felicia remained beloved by the NAL scientists but, alas, would not live long to enjoy her retirement. She passed away in May 1972 from a ruptured abscess on her intestinal tract. May she be enjoying much well-earned hamburger meat in the ferret afterlife.

0 Comments